"What's your favorite film?"

I can hear feel the judgement of true cinephiles when I respond.

They don't even have to say anything. I know.

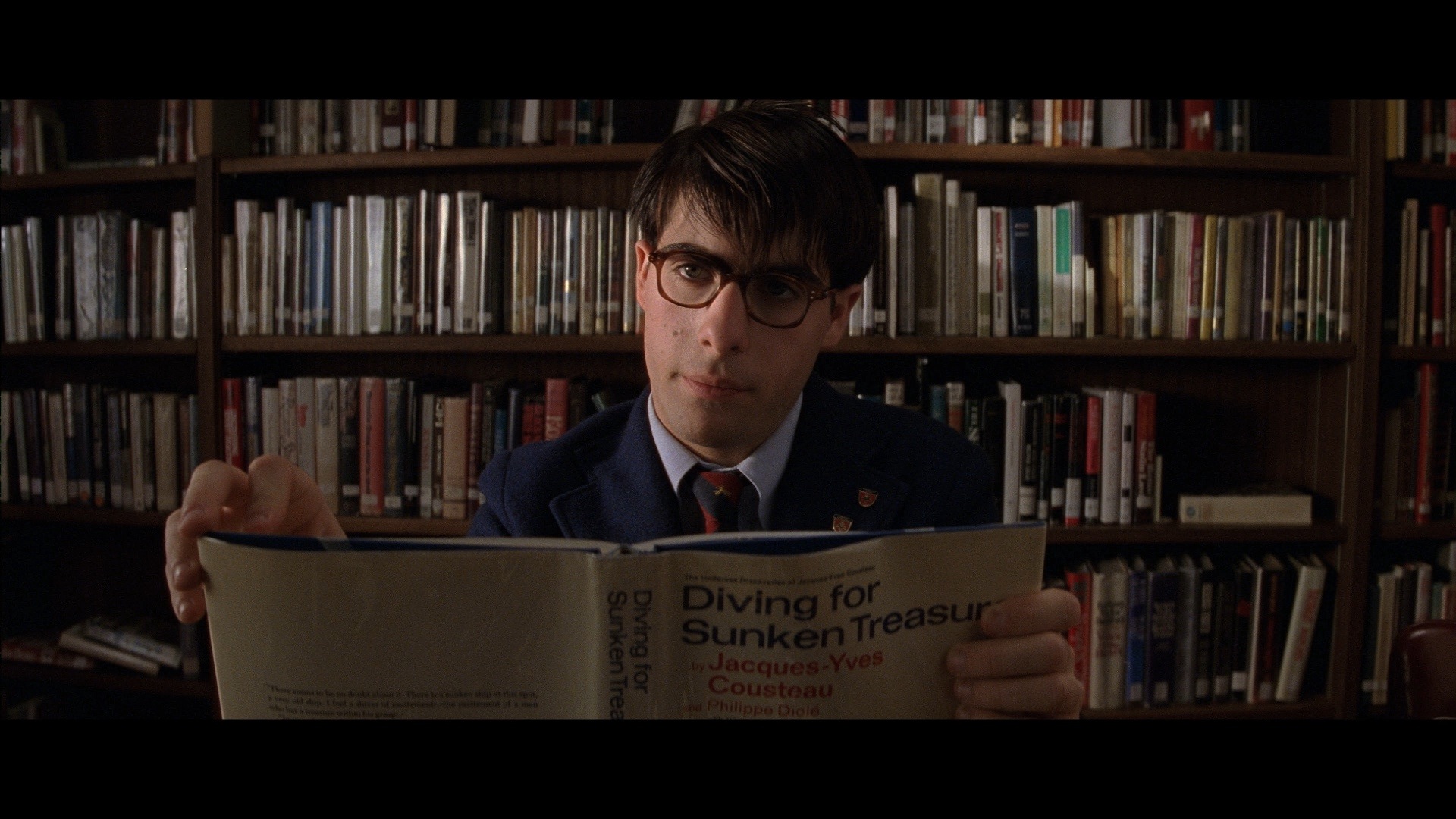

I know the implications of RUSHMORE being my favorite film of all time. For young filmmakers, cinema fags, and movie buffs, picking a Wes Anderson film as you favorite is akin to claiming CITIZEN KANE as the greatest film ever made.

Been there, done that.

"I've matured past Wes Anderson," they may as well say as they vigorously and dismissively wank in my direction.

Well, don't forget where you came from, motherfuckers.

You know at some point you thought Wes Anderson was the best thing to come along since sliced bread.

His style is so distinct that even untrained eyes know there's something very arty and unique about the characters and mise-en-scene in his films, and that's what's so attractive to teenagers with filmmaking aspirations. Hell, the guy has inspired the better part of the generation after him to become filmmakers. Like a lot of influential filmmakers, there are films Before Wes Anderson (B.W.E.) and there are films After Wes Anderson (A.W.E.) Like him or not, that's pretty evident by the innumerable color-by-numbers, indie, quirky comedies that have been released in the last few years.

...and that's the source of a lot of hatred for him. There are plenty of grievances you could have against Mr. Anderson, but being influential shouldn't be one of them.

*Steps down from soapbox*

Ok.

Despite what anyone else may think of Wes Anderson, he played a big role in my formative years, and he did it with RUSHMORE.

I already wanted to be a filmmaker by the time I saw it for the first time, but it brought the most obvious part of filmmaking to my attention: the camera. The way Anderson and his long-time cinematographer, Robert Yeoman, frame shots floored me. I had never heard of the rule of thirds. I had never heard of mise-en-scene. I could just tell there was a meticulous thought process to the placement of the camera and the framing of characters within the shot. I thought about how virtually every shot could be frozen, framed, and put on a wall.

"It's so pretty," I thought.

"That's what I want to do! I want to create memorable images. Oh, shit. What's that job title?"

Cinematographer. Director of Photography. D.P.

It should have occurred to me sooner. Of course, they don't just randomly set up a camera and start recording. Each shot is conveying information to the audience whether it be a mood, a clue, or motif.

This lead me to look at cinema in a completely different way. I began paying attention to how other filmmakers framed shots. I became interested in how information could be presented non-verbally. RUSHMORE became a filmmaking textbook of sorts for me, and it did what any good film should do: it made me want to watch more films.

I continued to pursue filmmaking for a few years. I tried to write screenplays and cultivate ideas, but without a way to properly edit (I was editing in-camera) I couldn't achieve even the most modest of filmmaking ambitions.

Enter RUSHMORE again.

What does Max do for the better portion of the film? Produce plays.

"I can write a play," I thought. We had a drama club at school. The instructor was my 11th grade English teacher, so I approached her one day near the end of the school year.

"If I write a play, will you help me put it on?"

"Sure. Why not? Work on it this summer and we'll start on it when school starts back in the fall."

Before I walked out of the classroom, she shouted towards me.

"Hey. It'll have to be cheap to produce though. We don't have much money."

Due to the budget restraints, I decided to set my play in a teacher workroom of a high school. It was a comedy. I wrote all summer on our desktop computer. I didn't even use script writing software; I used Word. I would put my RUSHMORE DVD in the computer's disk drive, put my headphones on, and write. I did this everyday.

I've probably listened to the movie more times than I've actually seen it.

Long story short, the play I wrote, and I did write a complete play, was never produced. After spending an entire fall of letting various English teachers read drafts, taking their notes, and revising the play, "Bored of Education," (see what I did there?) the drama teacher decided that she couldn't stay after school to supervise auditions or practices. Like many masterpieces, my grand opus of the stage was halted in development hell.

But something very important and positive came from that experience...I completed something. I wrote a 30+ page play. That was more than I had ever written, and for the first time, I had written more than one draft of a project.

That brings me the most enduring quality of RUSHMORE. To me, it's a film about writing. It's about how Max takes his experiences and the people he meets and incorporates them into his final play of the film, HEAVEN AND HELL.

There's a really nice sequence before the play where Anderson shows us every character (even ones as minor as the unnamed police officers that arrest Max at school) at the premiere of the Vietnam War-based production.

Max's takes center stage and dedicates his play to the memory of his dead mother, Eloise Fisher, and to Edward Applebee, "a friend of a friend."

When the play starts, it's loud and extravagant, just like Max, but upon closer inspection, several seemingly arbitrary moments from earlier in the film begin to resurface.

Dirk's character does the owl call he did before he and his friends threw rocks at Max.

Then there's the appearance of Max's cherished Latin phrase, "sic transit gloria."

The very setting of the play is a call-back to a conversation between Max and Mr. Blume about Mr. Blume's time in the Vietnam War.

MAX: Were you in the shit?

MR. BLUME: Yeah. I was in the shit.

Max's introduction to the play is even a call-back of sorts to a particularly nice conversation he and Ms. Cross have earlier in the film about Mrs. Fisher and Edward Applebee. "We both have dead people in our families," Max says after learning that her husband drowned a year earlier.

HEAVEN AND HELL is about loss, and Anderson shows how Max incorporate his experiences into the play. Back when Max is first shown working on the play, it's during a "things are looking up" montage (for lack of a better term.) It's presented as an act of self-improvement. There's very much a theme of writing as a form of healing, growing, and moving on after a loss.

Max is dealing with the second great loss of his life, his first love. Ms. Cross is still dealing with the loss of her husband ("she's in love with a dead guy anyway," Blume says earlier in the film.) Mr. Blume is dealing with the loss of his marriage, and Mr. Fisher is still dealing with the death of his wife.

Directly and indirectly, all these people are healed at the play. Max, as a measure of showing he's finally moved on, sends tickets to Mr. Blume and Ms. Cross in adjacent seats. During the intermission they make amends while having coffee and cigarettes together.

After the play, Mr. Fisher sparks up a romance with Max's new math teacher. They cut a rug on the same dance floor that Max and Ms. Cross eventually share as they reconcile completely.

As the curtain drops on the film, we're left knowing Max is going to be ok. He wrote about his experiences (indirectly of course) as way of coping with them and moving on.

Like any coming-of-age film RUSHMORE is about growing more than anything. Even though I've grown as a film lover and am constantly working to expand my knowledge, I'm still not going to forget (or be ashamed of) where I came from.

Thank you.

*claps* Hooray! Well done. I really need to see Rushmore now (and also start a blog of my own up).

ReplyDelete